The Desire to Be An Important Person

The changing meaning of importance from Ancient Greeks to Digital Networks

Dear reader,

The urge to be regarded as a person of consequence is as ancient as social life itself. Yet the meaning of “importance” has changed so profoundly that a medieval knight, a nineteenth‑century industrialist, and a contemporary social‑media celebrity would scarcely recognise one another’s standards of esteem. Taking a long‑range view from classical antiquity to the digital age, this essay explores how human communities have defined, sustained, and contested the condition of being important.

Ancient Times

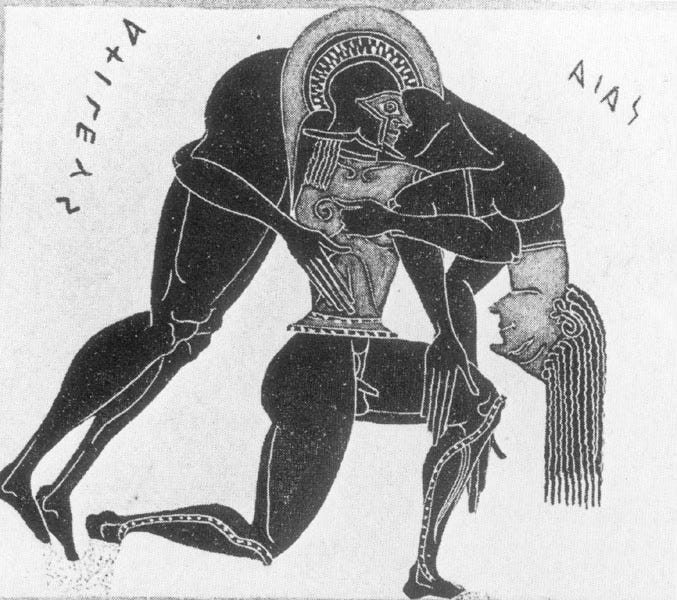

In Homer’s epics, the Greek ideal kleos, the fame heard on other people’s lips, of the earliest yardsticks emerges as one of importance. Prestige is measured less by lasting achievements than by whether one’s name lives on in song after death. A warrior who dies young may still be deemed superior if a bard’s memory carries him into the future. The same dynamic appears in China’s Shi Jing of the Zhou era: court historiographers immortalise rulers and ministers not merely for their rank but for exemplary conduct. In both civilisations, record‑keeping institutions become engines that convert transient deeds into cultural capital. To be important, in short, is to enter the record.

Rome shifts the calculus by grounding renown in civic life. Dignitas and auctoritas accumulate through magistracies, military triumphs, and oratory in the Senate. Cicero’s letters reveal senators pursuing priesthoods and triumphs less for financial gain than to secure supremacy in their lineage. Roman culture introduces the notion that legal precedence can entrench reputation: when the Senate awards a general a triumph, his statues and titles acquire a quasi‑juridical permanence. Importance thus comes to mean inscription both in marble and in law.

Late Antique Christianity

Christian late antiquity rewires these values. Martyrdom confers the highest importance on the seemingly powerless: Blandina, a slave girl tortured in Lyon, stands in hagiography beside emperors. In De Civitate Dei Augustine argues that worldly rank is fleeting and true importance lies in proximity to divine grace. The monastic system puts this doctrine into practice. Illuminated manuscripts render mostly anonymous scribes immortal while kings depend on monks’ prayers. Europe therefore lives within a dual economy of eminence: the feudal lordship and sanctity. It is a tension that nurtures reforming energies in figures such as Francis of Assisi, who renounces wealth yet rivals princes in charisma.

The Renaissance and Early Modern Times

The Renaissance revives classical fame but infuses it with humanist openness. Petrarch’s obsession with literary immortality turns authorial voice into a new path to importance. Print capitalism accelerates the trend: the advent of movable type in Venice sends thousands of copies into circulation, weakening the aristocracy’s monopoly on attention. At the same time the Ottoman court refines the Şehname tradition, addressing an elite readership and controlling the diffusion of prestige. The episode shows that importance can still be produced through regulated circulation rather than mass publication.

The Enlightenment and early industrial era anchor prestige in secular and national foundations. While Adam Smith praises the “man of system,” the French Revolution elevates the law‑making citizen as the archetype of public importance. The same period also births modern anonymity: mass armies and factories render many lives interchangeable, sharpening the appetite to stand out. Napoleon grasps this psychology, cementing loyalty by distributing decorations such as the Légion d’Honneur. The state proves it can certify esteem much as it mints coin.

The Modern Times

In the nineteenth century, the newspaper assumed the role of arbiter. Papers run by Hearst, Zola, or The Times can fabricate or destroy reputations overnight. A back‑bench parliamentarian discovers that column inches matter as much as votes. Max Weber theorises this shift as the “routinisation of charisma”: personal magnetism still counts, yet public recognition depends on bureaucracy and the press. The sociology of importance appears less as a heroic narrative, more as a scarce resource allotted by institutions.

Mass democracy universalises the quest for renown but supplies new filters: cinema, radio, and later television. Walter Lippmann speaks of the “manufacture of consent,” granting media barons the power to build prestige synthetically. Meanwhile, anti‑colonial, civil‑rights, and feminist movements broaden the circle of visibility and redefine importance. Rosa Parks’ refusal to surrender her bus seat propels an ordinary seamstress ahead of governors in moral authority, and the potency of her gesture lies in overturning society’s ranking of actors.

The Digital Networks

Digital networks fracture hierarchy anew.

Algorithmic feeds measure importance through clicks, likes, and network centrality. Metrics are refreshed hourly, making fame more fluid. A teenager on TikTok may reach audiences larger than those of most prime ministers, yet platform volatility means importance can wilt as swiftly as a flower.

Pierre Bourdieu’s triplet of economic, social, and cultural capital needs updating: the capacity to trigger network effects (algorithmic capital) now co‑determines prestige. Nor is this logic confined to influencers. Citation analytics rate a scholar’s “impact”, venture capital tallies a start‑up’s “runway importance”, and even diplomacy tracks summit‑day “tweet engagement.”

Persistent zones of lasting esteem nevertheless endure. Nobel prizes, military orders, and episcopal appointments still command long‑term respect because they remain scarce, ceremonial, and, however imperfectly, insulated from analytic volatility.

The emerging tension is epistemic: will importance be determined by the crowd or by gatekeepers?

Wikipedia’s notability guidelines draw upon both principles, demanding institutional references while relying on the collective judgement of volunteer editors.

So What Lies Ahead?

One main force seems poised to complicate the history of importance once again.

Generative AI will further cheapen content production, saturating the attention market and making it harder to stand out. Academia may therefore revalorise bodily presence, such as fieldwork and conferences, while digital creators lean on the ephemerality of live streams to preserve a momentary “aura.”

History proves that the criteria of importance are never immutable and each era reshapes them according to its technologies, moral vocabularies, and institutional needs. Yet the record also shows that permanence correlates with contributions perceived to outlast the contributor - be it a reformed law, a healed patient, or a melody immune to the erosion of time.

Once the pursuit of importance sheds ego, it reduces to the question: “Whose life benefits the greatest number?” If your actions can answer that question, history, capricious though it is, tends to remember.

Thank you for reading,

Khalil,

Brisbane 2025