How to solve your work-life balance problem like a Roman

Dear reader,

Pause a moment and listen to the background hum of your life. A calendar packed with meetings, inboxes that refill overnight, the silent competition to look busy - these have become the civic drums of the twenty‑first century. Yet two thousand years ago, Roman writers were already warning that relentless busyness can hollow out a citizen as surely as neglect can rot a bridge. They proposed a double cadence: negotium and otium.

Romans judged a life successful only when both notes could be heard in harmony.

Negotium is Latin shorthand for nec‑otium, “the absence of leisure.” To a Roman ear the word carried neither pride nor complaint. It simply named all outward work that kept the commonwealth alive. Senators drafted laws, engineers repaired aqueducts, vigiles patrolled alleyways with oil lamps, farmers harvested olives to feed the city. Cicero counted even heated debates in the Forum as negotium, because public oratory was a kind of civic engineering that patched cracks in the republic’s moral masonry. The common thread was service. A task mattered not for its paycheck but for its contribution to res publica, the shared thing that was Rome.

That standard travels well. Today’s equivalents stretch far beyond salaried employment: a teenager teaching chess at the library, neighbours organising a weekend litter‑pick, volunteers cataloguing archival photographs so that local history is not lost to mould. Each act fortifies a seam in the social fabric.

The danger arises when we confuse constant motion with genuine contribution.

Because the modern city runs on notifications rather than trumpets, it is possible to be frantic all day and still leave nothing standing by nightfall. Seneca foresaw the trap: “People are thrifty in hoarding their money,” he wrote, “but wasteful in squandering their lives.” Negotium performed without measure devours the very self whose energies it consumes.

Enter otium, often mistranslated as idleness. The Romans never equated it with dalliance. Otium was protected time for pursuits that deepen the mind and soften the passions: reading a scroll of philosophy, tuning a lyre, writing letters that would outlive the writer, strolling a colonnade while testing an idea against a friend’s counter‑example. Cicero spoke of otium cum dignitate (leisure with dignity) insisting that such intervals were not an escape from duty but a return to first principles. In otium one remembered why the aqueduct mattered in the first place.

Our era needs this counterweight no less. A dawn meditation before the algorithm’s murmurs begin, an hour of undistracted reading after supper, a notebook kept for questions rather than answers. All of these are contemporary forms of otium.

They reclaim attention, that most finite civic resource, from markets designed to monetise every glance. Practised seriously, otium is not passive recuperation but creative fermentation. Ideas steep, prejudices loosen, empathy grows rootlets. When the thinker steps back into negotium, decisions emerge clearer and projects more humane.

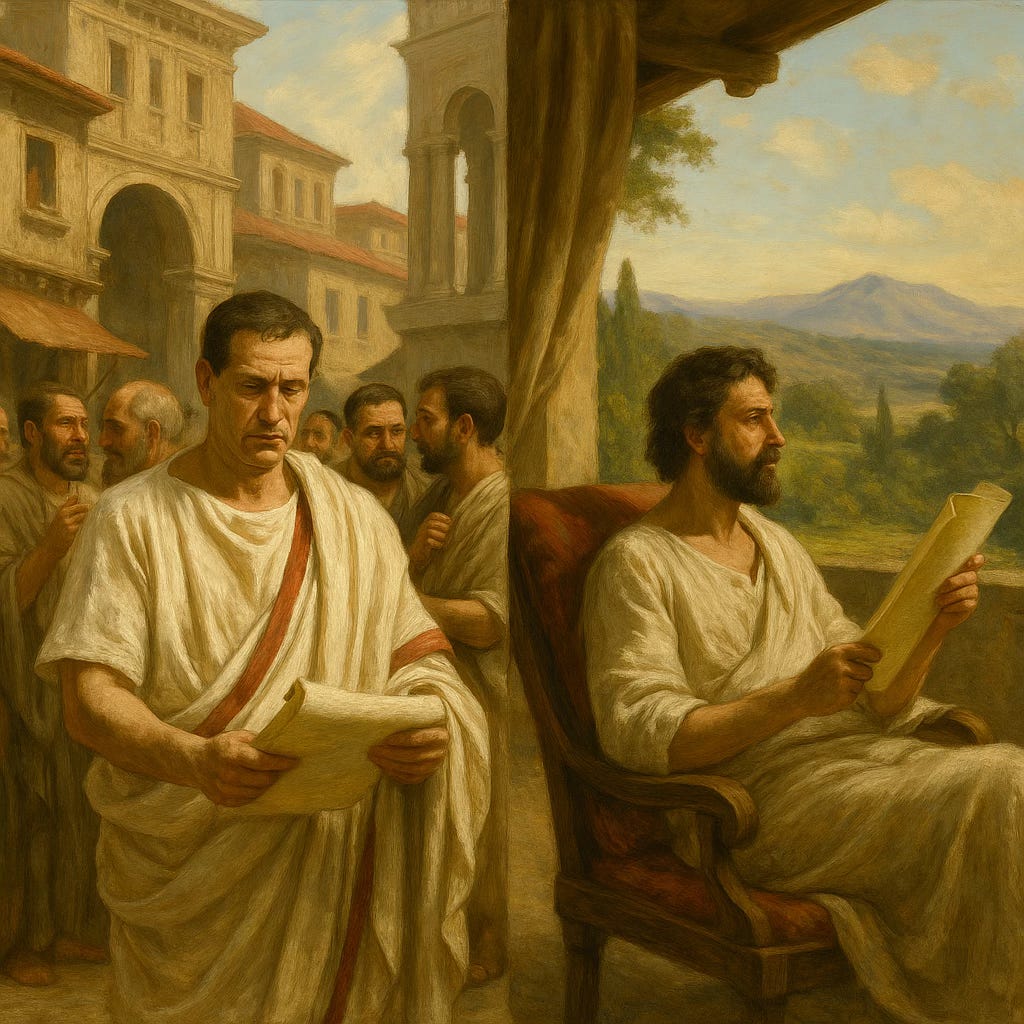

The rhythm between the two poles, not the poles themselves, carries the wisdom. Action without reflection ossifies into routine. Reflection without action however, sours into vanity. The Romans visualised the relationship as breathing. Exhaling into public work, inhaling in private study. Many of them literally timed their day by this logic. Marcus Aurelius answered petitions at dawn and wrote his Meditations after midnight. Pliny the Younger spent the afternoon supervising quarry contracts, then retreated to his Tuscan villa to describe sea birds puncturing the dusk.

So, how can a modern citizen restore that cadence amid smartphones and shift work?

Begin with the small gatekeepers. Set your phone to deliver messages in scheduled batches, echoing the way Roman secretaries once sifted correspondence so their patrons could think. Rotate volunteer duties. Coach football this month, hand the whistle to someone else next month, so that community benefits while your household supper remains unhurried. Declare sunrise and sunset as inviolate quarters of an hour for breath and thought. Remember that ancient farmers looked to the same sky to pace their toil and there is wistom in that.

Let the larger calendar breathe as well. In spring, take on outward‑facing projects. Organise a neighbourhood seed swap, host an open‑air reading of local poets, repair a broken footbridge before summer floods arrive. Rome scheduled its great festivals when the Tiber ran full and the grain sprouted. The public joy was a form of civil maintenance. Reserve winter evenings for inward crafts like binding notebooks, studying a dead language, practising slow scales on an instrument. These quieter labours mirror the dormant fields, storing sap for a future flowering of public energy.

One might protest that such balance is a luxury. Bills and deadlines do not pause because you wish to imitate a Stoic. True, but even the busiest Roman knew debt collectors and military drafts. They carved otium from necessity, not excess. A single candle was enough for Seneca to copy out Euripides and a shaded portico sufficed for Cicero to rehearse a speech.

Our impediment is therefore seldom time itself, but the psychical noise that blurs its contours.

Silencing that noise, however briefly, multiplies whatever hours remain.

What, then, is won by this ancient discipline besides a pleasant change of pace?

The Romans answered with one word: humanitas. To them it meant more than civility. It was the full maturation of human faculties, reason, imagination, sympathy, into a force that could radiate beyond the self. When negotium and otium feed each other, humanitas blooms almost incidentally. A volunteer who reads widely becomes a kinder organiser and a reflective artist who mentors children finds fresh colours for the canvas. The circle expands.

Here is a modest experiment you might adopt after finishing this letter. Choose a single civic chore (perhaps volunteering to train the youth?) and a single contemplative habit (say, keeping a short daily log of questions that troubled you). Perform each for sixty consecutive days, allowing neither to invade the other’s slot. Observe how the letter grows sharper as the journal distils your motives, and how the journal grows steadier when the letter demonstrates effect. By the end you will have replicated a miniature of the Roman cycle, and you will feel the old city’s arteries beating inside your own schedule.

We cannot resurrect the Forum or rebuild the aqueducts by hand (and why should we? The past is past), but we can inherit their logic. The equilibrium of negotium and otium is not nostalgia. It is a tool, as constructive now as masonry or rhetoric was then. In an age that measures worth by output graphs, it reminds us that output alone is sand if not moulded by silent reflection.

In a culture that glorifies self‑care, it reminds us that the self is healthiest when it passes energy into the civic bloodstream.

May your days therefore alternate like Roman arches: one stone of purposeful labour, the next of unhurried thought, each leaning on and supporting the other. Where the two meet, a doorway opens - wide enough for individual contentment to walk outward, and for collective well‑being to walk in.